Metacognition and student-centred digital learning elicited intriguing discussions among Nepalese teachers in training workshops.

Metacognition has re-emerged in educational discussions becoming one of the central concepts in the context of increased digital learning. Such contexts require enhanced digital competence, including the ability to regulate metacognitive processes i.e. being aware of one’s own learning process (Fogarty & Pete, 2020). Metacognitive dimensions are displayed in the ability to regulate one’s cognitive, motivational and emotional behaviour towards achieving learning goals. In other words, students should set up learning goals, plan and process their activities according to the plan, monitor their progress by reassessing or changing plans, and observe their affective behaviours (Azevedo et al., 2013; Fogarty & Pete, 2020). To obtain and uphold such abilities is particularly challenging in digital learning environments.

Digital learning connects pedagogical actions to various digital techniques and technologies in education, including mobile devices, tablets, MOOCs, virtual laboratories, simulations, and many different apps (Haleem et al., 2022).

In Nepal, during the time of COVID-19 pandemic and beyond, digital learning has been emphasised at both government and non-government levels (Gharti, 2023), resulting in some progress in improving Nepalese teachers’ digital competences. To contribute to the government’s ambitions, two Nepalese universities, along with their Finnish counterparts, had an opportunity to support the integration of ICT into pedagogical actions in Nepal.

Several workshops were held across Nepal to promote the integration of ICT and 21st-century skills into the learning process during 2023-2024. Despite remoteness and difficulties in accessing some areas (travelling might take two days), the country’s all seven provinces and hundreds of teachers were reached. The workshops were designed to be interactive, promoting principles of connectivism by encouraging group interaction and open dialogues when solving problems and understanding data. Connectivism emphasises the role of digital tools in modern education, the importance of networks and connections, and active students’ engagement and self-directed learning (Siemens, 2005). Keeping these principles in mind, workshop participants discussed many aspects related to digitalisation of education and student-centred learning.

However, the concept of metacognition sparked intriguing questions among the Nepalese workshop participants. Questions were raised about the meaning of metacognition, its role in teaching and learning processes, and strategies teachers could use to foster metacognitive development among students. In this article, we focus on discussing the teachers’ questions related to metacognition, but first, we describe the context in which the workshops were conducted in Nepal.

Workshops in seven provinces in Nepal

Workshop training has been conducted in all seven provinces in Nepal, reaching hundreds of teachers in total. The provincial government agency, the Education Training Centre, and local campuses have played a crucial role in coordinating the workshops. The training reached participants from very remote areas, including the Gaurishankar rural municipality in the mountainous region and Solukhumbu district, where Mount Everest is located, which takes two days to travel by bus.

Inclusivity was a key consideration in the training. The aim was with at least 50 % of the trainees being female and each district represented by at least two teachers. However, the female-to-male ratio was not fully achieved due to some socio-cultural and other factors. Some of these factors in Nepal, as noted in the study by Bhatta (2024), include school leaders not allowing female teachers to participate in training or females having other burdens at home and too many work responsibilities.

The participating teachers were already somewhat familiar with certain technical and 21st-Century Skills (21stCS). For instance, a school in the Gaurishankar village municipality has transformed its educational approach from a traditional “Four Walls” model to a “No Walls” model. In general, among the Nepalese teachers, the main challenge is integrating 21stCS into pedagogy and recognising their importance, especially in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic. Unfortunately, many teachers either completely or partially abandoned these skills after the pandemic, failing to recognise their importance in utilising them in their current teaching practices.

Two universities, Tribhuvan University, the oldest university in Nepal, and the Nepal Open University (NOU), a young institution operating in an Open and Distance Mode, collaborated with Jamk and HAMK Universities of Applied Sciences in the 21st Century Skills Nepal -project to develop a new curriculum and teachers’ professional development training. Upon the approval of the syllabus by the university authorities, a comprehensive training manual was meticulously developed by both universities. The primary objective of this initiative was to incorporate digital skills, technology, and 21st-century skills into teaching and learning activities at schools. To achieve this, training workshops were organised. Dr Jiban Khadka, one of the authors of this article and a team leader at NOU, was involved in this initiative, thus, the examples in this article are drawn from the context of his workshops.

Training workshops: Integrating content, pedagogy and technology

The aim of the workshop training was to revive and rejuvenate the use of ICT and its integration with 21st-century skills in daily classroom activities. The workshop lasted two days and comprised eight sessions in total. The workshops were divided into three main sections. The first section introduced ICT and 21stCS. The second section provided a framework for these components, enriched with examples and activities related to ICT and 21stCS. The third section required participants to prepare and present an activity as part of a lesson plan, serving as an assessment.

As the training programme progressed, critical pedagogy was integrated in response to the teachers’ demand for content that fostered critical thinking and problem-solving. Presentation was conducted to broaden the understanding the 21stCS to include Ways of Thinking, Ways of Working, Ways of Living, and Tools for Learning and to associate 21stCS with ‘Critical Thinking’ and ICT.

The workshop fostered a participatory, collaborative, and democratic environment, encouraging participants to interact, share experiences, ask questions, and construct knowledge in the sessions. This engaging environment facilitated learning on how to involve students in the classroom using technology integrated with 21stCS. The workshop primarily utilised digital tools, enabling participants to learn about different tools and techniques for searching resources from the internet, presenting, sharing, interacting, socially networking, and assessing learning. Furthermore, the sharing of cultural and professional experiences on local practices in schools were notable events in the training sessions.

Participants actively engaged in various activities to test learning with connectivism, such as using Google Meet, and sharing their experiences and ideas using Mentimeter and Padlet. To energise participants and motivate them towards the workshop, cultural dances were introduced in the mid-session. Amidst these digital and participatory activities, the trainers also initiated discussions on abstract pedagogical concepts such as metacognition, that prompted teachers asking questions like: What does it mean? Why is it needed? And how can teachers support students’ metacognition?

What does metacognition mean?

The concept of metacognition, extensively studied in recent decades, is re-emerging in educational discussions in the context of increased digital learning. Metacognition is a multifaceted and multidimensional concept, as indicated by earlier empirical studies (Efklides, 2009). It is viewed as a high order thinking skill and involves being aware of one’s own thought processes (Fogarty & Pete, 2020).

While researchers may have slightly different definitions of metacognition (Kallio, 2020), the two-component model of metacognitive knowledge and metacognitive regulation has gained widespread acceptance. Metacognitive knowledge involves understanding the types of knowledge and skills required for specific tasks. It encompasses knowing what you need to learn and how to learn it, including an understanding of various learning strategies. On the other hand, metacognitive regulation refers to the ability to apply and adjust different learning skills as needed. It involves managing one’s own learning process, adapting strategies based on the task at hand, and controlling one’s learning pace and direction (Bwalya, 2021).

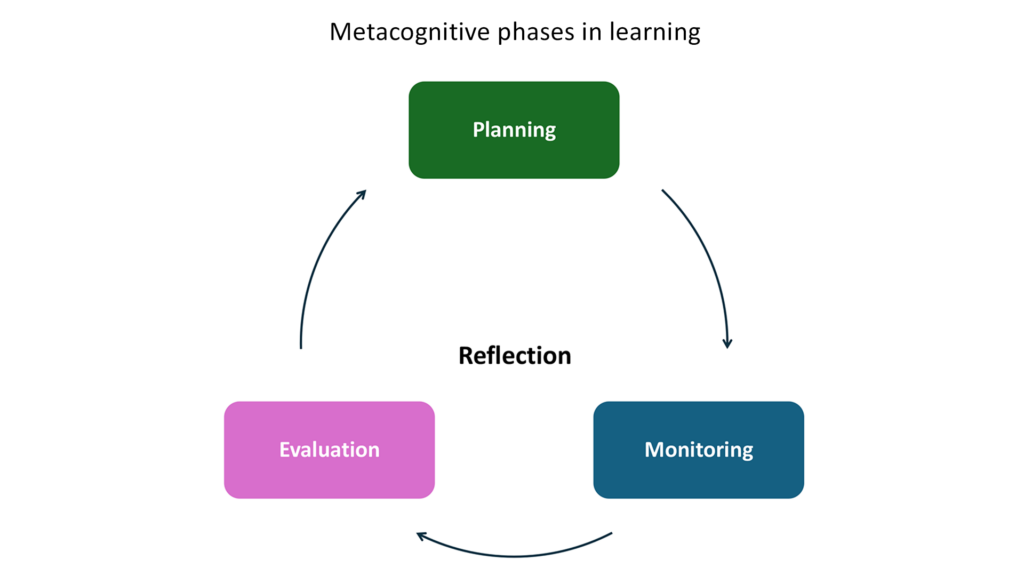

In their research-based book on Metacognition: The Neglected Skill Set for Empowering Students, Fogarty and Pete (2020), outline three vital aspects of metacognition for learning: planning, monitoring, and evaluating. See Figure 1.

The metacognitive phases of learning start with learners devising a plan to achieve their learning objectives, which includes selecting appropriate learning strategies. As they progress, learners continually monitor their own learning, assessing how effectively they are meeting their goals and adjusting their strategies as necessary. The evaluation phase involves learners critically assessing their learning outcomes and making further strategy adjustments. Reflection is an integral part of each phase, and the ability of learners to effectively adapt their learning strategies plays a crucial role in determining the success of the learning process (Fogarty & Pete, 2020; Winne & Azevedo, 2022).

Why is metacognition essential in the teaching and learning process?

There is a broad consensus among researchers that metacognition plays a pivotal role in all phases of learning (Efklides, 2009; Reingold et al., 2008). Therefore, it should be emphasised at every educational level to meet the demands of 21st-century learners. The ability to reflect on one’s own thought processes is a critical skill in any learning situation, leading to learners becoming metacognitively aware of their learning. In other words, learners should understand how, what, when, and why to study and be capable of regulating learning within different subject areas (Kallio, 2020). This metacognitive awareness is explicitly evident in the development of expertise. The literature indicates that experts in any field possess highly developed metacognitive skills (van Velzen, 2012), which are manifested in their heightened awareness of themselves as learners, as well as their ability to reflect on their learning strategies and monitor their progress.

Research on metacognition suggests that it can enhance learning efficiency by emphasising students’ cognitive processes, such as memory, attention, activation of prior knowledge, and task completion (Chew & Cerbin, 2020). It also encourages students to become critical thinkers and fosters the development of their self-regulation and self-awareness (Halmo et al., 2024). Learners who employ metacognitive practices enhance their abilities to transfer or adapt their learning to new contexts and tasks by gaining a level of awareness that transcends the subject matter (Chick, 2013).

In essence, metacognition serves as a roadmap for learning. It not only guides students on what to learn but also instructs them how to learn, thereby making the learning process more effective and meaningful. Despite this knowledge, literature seems to suggest that university students do not engage in metacognitive strategies in their learning (Anthonysamy et al.,2020; Boser, 2018). This is evident especially in online learning, where the demands to self-regulate metacognitive strategies are higher than in traditional settings (Anthonysamy et al.,2020). Studies have shown that students lacking self-regulation have the inability to transfer their learning strategies from a traditional to an online learning environment and are said to lack metacognitive skills (Lilian et al., 2021). Thus, the use of metacognitive strategies in all learning settings is crucial.

How can teachers support the development of metacognition of their students?

Teachers’ own capabilities of adapting various teaching and learning strategies to develop their students’ metacognitive strategies play a significant role in helping students become independent and strategic learners (Oven & Vista, 2017). However, research literature underscores that teachers’ awareness of their own metacognition is key to understanding the importance of metacognitive skills (Kallio, 2020). Once this awareness is gained, teachers can offer several general and subject-specific strategies to support their learners’ metacognitive skills.

Teachers can promote general awareness of metacognition by explaining and discussing the importance of metacognitive knowledge and metacognitive regulation and how these aid in becoming a self-regulated learner. However, discussions alone are not sufficient. Teachers should model their own metacognitive processes and allocate time for reflective discussions. Providing students with opportunities to reflect their own successes and failures, both individually and in group, promotes metacognitive awareness.

In general, teachers can employ numerous strategies and activities to foster the development of metacognitive skills both in traditional and digital learning environments. Below are a few easy-to-use strategies that were used in workshop training and some developed online courses in Nepal:

- Keeping a personal learning diary or journal, which could be guided by a teacher by introducing reflective questions to students

- Using a KWL chart – what you know, what you want to learn, what did you learn.

- Employing the thinking aloud method.

- Implementing paired problem-solving.

- Practising reciprocal teaching –small groups of students work cooperatively and take turns playing the teacher questioning and summarising the material being studied.

- Facilitating reflective discussions.

Final thoughts

Having been involved with the project’s initiatives and conducted several workshops, we noticed the importance of connecting pedagogy to technology. Promoting student-centred, digitally-enhanced learning is not an easy task. Pedagogy based on connectivism can offer a framework to emphasise the role of digitalisation in learning, while also recognising the importance of students’ self-directed learning. In other words, enhanced metacognitive skills are needed in all learning environments.

Teachers who participated in the workshops gained more awareness of metacognition and its integration in online learning environments. We noticed many teachers were excited to try new digital tools in their teaching and consider how to best support their students’ thinking skills. Still, there are many teachers in Nepal who have not had opportunities to participate in such training, therefore we hope the work continues through teachers’ professional development training.

The questions raised by the Nepalese teachers in the workshops on the role of metacognition are highly relevant for all educators. Thus, promoting metacognitive awareness and lifelong learning processes should be a high priority in teacher education programmes globally. This would enable teachers to create a culture of teaching and learning that produces thoughtful and reflective students. As we discussed earlier, there are various strategies teachers can use to enhance students’ metacognitive skills when the primary aim of learning is enhancing the quality of students’ thinking.

Conducting training workshops in Nepal was one of the actions in reaching the overarching aims of the 21st Century Skills Nepal -project in strengthening the capacity of higher education in Nepal and enhancing equal access to education through digital learning opportunities. The project supported increasing digital competences of university teachers at Tribhuvan University and Nepal Open University by cocreating a new Master level programme in digital pedagogy for the 21st century. The project also developed a guidance and counselling module and a MOOC for in-service teachers to help them understand how to accelerate learning of students from disadvantaged communities.

More information:

If you are interested in discovering more on metacognition, there are several websites that describe teaching strategies for improving students’ metacognitive awareness.

- For example, MIT Teaching + Learning Lab and Cambridge International Education Teaching and Learning offer several examples of implementation.

- An evidence-based teaching guide can be found in the CBE Life Science and Education journal.

- Further examples and recommendations on implementation can also be found on the Yale Porvu Center for Teaching and Learning.

Developing Pedagogy for 21st Century Skills Nepal

Our goal is to strengthen the capacity of higher education in Nepal to enhance equal access to education through digital learning opportunities. See also the Training manual for the Integration of ICT and 21st century skills in education.

The Developing Pedagogy for 21st Century Skills Nepal -project has been funded by the Ministry for Foreign Affairs of Finland, through the Higher Education Institutions Institutional Cooperation Instrument (HEI ICI), which is administered by the Finnish National Agency for Education.