Finnish Education System – Learning How to Teach

The back cover of the book Finnish Education System – Learning How to Teach (Adiputri, 2023a), published on 17 May 2023, compares education between Indonesia and Finland by an analogy: in Indonesia, most teachers cannot swim but they must teach students how to swim; while in Finland, students learn from the swimming experts. For us, the statement has double effects: it is tragic, yet at the same time, it builds an admiration towards teachers in Indonesia to tackle their situation.

In Indonesia, education emphasizes ranking, competition, and hierarchy (Adiputri, 2023b), while in Finland, school subjects seemed easy. We did not see school children opening their schoolbooks at home, except for doing homework yet they thrived, enjoyed schools and had good grades without hassle. We observed such differences and wanted to understand more about how things work at school. That was the basis of the first book “Finnish Education System- Learning How to Learn” (Adiputri, 2019).

This first book has been popular in Indonesia, giving opportunities for teachers and educators to know the Finnish education system deeper, with examples of personal confusion related to reality in the classrooms, Finnish language, climate and adjusted the lives as Indonesians living in Finland. Thus, the book had been reprinted four times since, and around 5000 copies are already in public (see also Adiputri, 2021).

The second book, which is the topic of this article, was written based on our experiences in studying and teaching in Professional Teacher Education in the Digital Era at Jamk UAS. One of us was the student (Adiputri) and another was the teacher educator (Burns). The book covers what and how the pedagogy and the programme were learned, with study reflection. Adiputri informed readers about struggles, challenges, and inspirations from the study. The book contains valuable information about current pedagogy in practice.

Teachers and education system in Indonesia

In theory, teachers have a distinguished position in Indonesia. Teaching is a noble job, teachers enjoy national teacher’s and education day, and the name teacher, guru in Indonesian, entails a positive image as someone who shows good practices and deserves to be followed. However, due to a hierarchal society, where power is based on “personal relationships between clients and patrons” (Adiputri, 2023b), there is always a division between national and local, elites and commoners, urban and rural with the former being considered better than later. In education, this means, for example, that teachers (or lecturers) at the university or higher education are considered better than teachers in primary schools. Having higher ranks and good grades are also considered better. Consequently, assessments can be manipulated, and parents, students and even teachers at school would do anything to push the grades higher, often involving bribing and money circulating at schools/universities and among teachers.

In Indonesia, position matters, so bureaucrats’ positions and headmasters are more valuable than as ordinary teachers, notably in big cities. Thus, the relationships between higher to lower positions are instructive. With such a hierarchal society, added to nepotism and corruption, it is relatively “easy” to bribe personnel at the higher level to give certain positions. University students are not interested in becoming school teachers and choose to work at state or regional institutions, or teachers at high schools and universities. Those who fill the positions of school teachers are mostly less passionate about teaching, and seek for better opportunities. Teachers’ salary is usually low in Indonesia. These aspects demotivate young persons to apply for teacher positions, notably at primary schools.

To complicate matters, education in Indonesia is also known to face changes in national curriculum and policy . locally known as ‘ganti Menteri ganti kurikulum’ policy. The government is regularly changed every 5 years, and thus, it has been common that the Ministry of Education will also change the curriculum. As the national government keeps changing the policies of assessment and curriculum, without involving teachers or supporting them to improve their competencies, it is likely that education in Indonesia will not change as much as expected.

Studying in the Professional Teacher Education Programme

The book began with a personal story of how Adiputri was admitted to the Professional Teacher Education studies. She was initially doubtful about the programme, as she had previously taken a pedagogy training course that was mandatory for teaching at the university level. She found that course uninspiring and merely participated, completed the tasks, and hoped to pass. She had her own reservations and perceptions about the program. However, she soon realized that her perceptions were wrong.

Adiputri underwent a positive transformation during the studies at Jamk. She learned to identify her own teaching style, contributed to the discussions, and acquired new skills such as making podcasts and applying Flipped Learning in her own class. She changed her perspective and seized the opportunity to grow as a teacher. She was proud of herself for the transformation. She not only overcame the challenges in finishing the studies on time, but also made tremendous efforts in accomplishing what was planned in the programme, despite her changing work situation. She felt guided and inspired by the teacher educators, who taught in organized way, yet presented intriguing subjects for further discussions and explorations. The programme was carefully prepared and structured, and Adiputri had access to all the information documents and references she needed. She could also contact the teacher educators through email and discuss with them any difficulties she faced and find solutions.

Launching the book

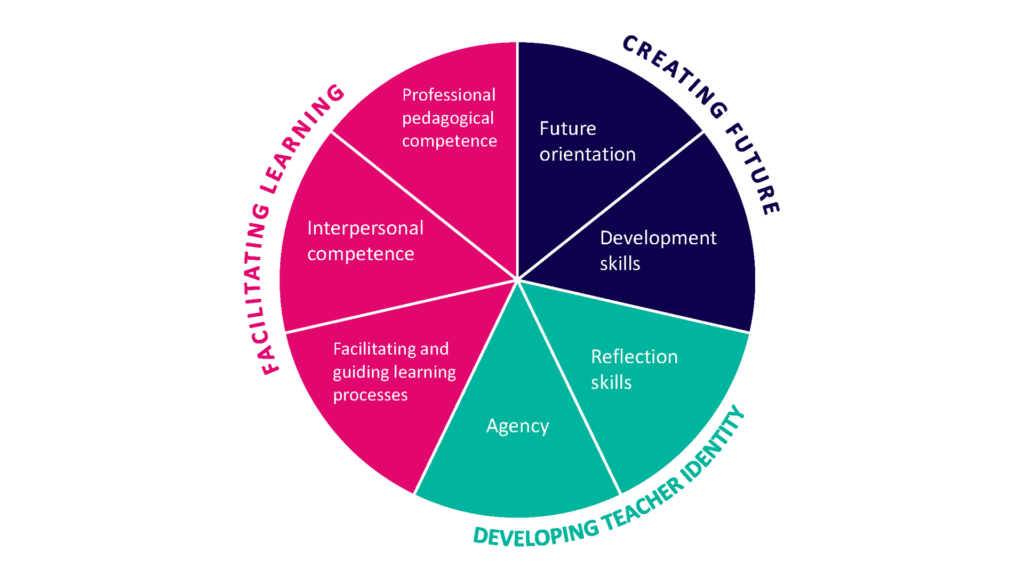

The book launching event, which attracted more than 1000 registered participants, was an opportunity for the author to present her insights on the three main teacher competence areas included in the programme: facilitating learning, creating the future, and developing teacher identity.

The author emphasized that teachers need to develop all these competencies and contrasted them with the current situation in Indonesia, where teachers are mainly expected to facilitate learning for short-term goals, such as passing exams. She also shared her personal experience of a learning assignment at Jamk where she learned to envision the future challenges and opportunities for education and society and imagine how schools and societies will be in 2050. In her book, she explained the importance of teachers being able to imagine societal changes and realize the future orientation in order to develop both their own as well as their students’ skills and identities (Adiputri, 2021).

The book consists of four parts: (1) Introduction to Professional Teacher Education, which provides an overview of Finnish pedagogy and teacher education; (2) What We Learned, which describes the courses, tutorials, and evaluations that the author and her classmates took; (3) How to Learn, which reflects on the development of teaching skills and knowledge through teaching practice and exposure to new concepts, such as digitality in education and hidden curriculum; and (4) Reflection, which summarizes the personal learning journey of the author.

Indonesia could not simply copy the Finnish model of education, but rather learn from its best practices.

The book highlights the importance of having a reliable learning environment that supports student teachers’ professional development. The author highlighted the facilities and technologies that Jamk offered, such as Panopto, a video platform for observing and sharing colleagues’ teaching experiences. Writing about the facilities was important, because Indonesian bureaucrats in the capital keep emphasizing the importance of digital skills for teachers, but for those outside Java island and big cities, even computer and reliable internet connections are hard to get. However, she also emphasized that technology is not a prerequisite for good teaching, but rather a tool that can enhance it.

In the book launch, Adiputri stated that “Indonesia could not simply copy the Finnish model of education, but rather learn from its best practices” and apply them in a way that respects the local values and culture. She argued that empowering teachers requires addressing the local needs and contexts of the schools, rather than focusing on ranking and competition among students, which would lead to more meaningful and sustainable learning outcomes (Adiputri, 2021, 70). She also acknowledged the potential “dangers” of adopting a post-colonial perspective that views Western models as superior to local ones. However, she expressed her hope that introducing Finland’s education system in the Indonesian language would generate more interest and curiosity among Indonesians. She concluded by saying that Finland is a respected country for Indonesians, and that learning from its education system would bring more benefits than losses.

Another theme of the book is the need for teachers to adopt a lifelong learning attitude and to create a future-oriented vision for themselves and their students. The author drew on her own experience of having her prior learning and achievements, such as scientific papers and conference presentations, recognized and accredited by Jamk, which helped her develop her teacher identity. She also urged teachers to be passionate about learning new things and to keep up with the changing demands of society. She reminded the readers that lifelong learning is a value that both Finland and Indonesia share, and that it can be implemented in different ways according to local needs and contexts. An Indonesian terminology Belajar Sepanjang Hayat, life-long learning, is important to be reminded and implemented for keeping the spirit alive in everyday life of teaching and learning. Adiputri explained that she learnt a lot with the help of reflection. She digested what she had learned in her reflective learning diary by adding notes, photos, links of videos and podcasts to acknowledge what she learned from the process. She discovered that the idea of reflecting is useful for us as teachers.

The book is written in an accessible and engaging style, with pictures, tables, and charts to illustrate the main points. It is intended for teachers, educators, policymakers, and anyone who is interested in learning from Finland’s best practices in education The author’s aim is not to replicate the Finnish model of education in Indonesia, but to learn from it and adapt it to suit the local values and culture.

Moving forward

By sharing personal experiences of teacher education studies at Jamk, the authors hope to empower teachers, not only in Indonesia, but also in other contexts, to learn Finland’s good pedagogy in practice. They invited teachers who had already completed their teacher training to compare and contrast their education with the Finnish training, and to find inspiration from the book that could be implemented in their own settings.

They argued that empowering teachers would have positive impacts on both teachers and students, as well as their immediate environment, such as considering their mindset, own family, own class, and own school. The host of the book launch also praised the author’s motivation to pursue professional teacher education at Jamk, despite having a doctoral degree and prior pedagogical training. He hoped that this would inspire other teachers in Indonesia to be passionate about learning.

In the book and in the presentation, Adiputri quoted Yuval Noah Harari (2018) on the importance of developing the 21st-century skills in education: critical thinking, communication, collaboration, and creativity (4 C skills). These skills are important for both teachers and students/learners. However, Adiputri pointed out the challenges of fostering collaboration and creativity in Indonesia’s education system, where competition is prevalent and where subjects that promote teamwork and expression, such as sport, handcraft, arts, and music, are reduced in the curriculum. She also referred to Lavonen (2020), who proposed seven categories of transversal competencies for education, which include “taking care of oneself, managing daily life; multiliteracy; digital competence; working life competence, entrepreneurship; participation involvement, building a sustainable future; thinking and learning to learn; and cultural competence, interaction, and expression” (p. 75). The authors noted that Indonesia’s national government mainly emphasized digital competence, while neglecting other aspects. They also acknowledged the difficulties of adapting to the changing demands of society for teachers in Indonesia, especially those in remote areas, due to the hierarchical and instructive culture.

In the final part of the book, the author reiterated the importance of learning how to learn, which varies from person to person. She emphasized the skills of interaction and collaboration with others (p. 250), as both Harari and Lavonen had suggested. She also hoped that the book would inspire the readers to appreciate their own way of personal learning, without comparing themselves with others’ skills and competencies (p. 264). “Just be yourself.”

The exaggerated claim that “in Indonesia, most teachers cannot swim but they must teach students how to swim whereas in Finland students learn from the swimming experts” has drawn attention and highlighted the paradoxical situation of Indonesian teachers, that while it is tragic, there is a sense of admiration for teachers in Indonesia. The widespread interest in the book on the Finnish education system, and the eagerness to understand the pedagogical principles of Finnish professional teacher education (by reading the books, attending the webinars, and engaging through social media) have shown us that teachers in Indonesia want to be empowered. We hope that this book can empower teachers in Indonesia, as some aspects can be implemented with a strong motivation from teachers and authorities to enhance the quality of education in Indonesia. One of the key factors is improving and supporting the teachers’ competencies.